inbox@english-medieval-antiques.com ©English Medieval Antiques

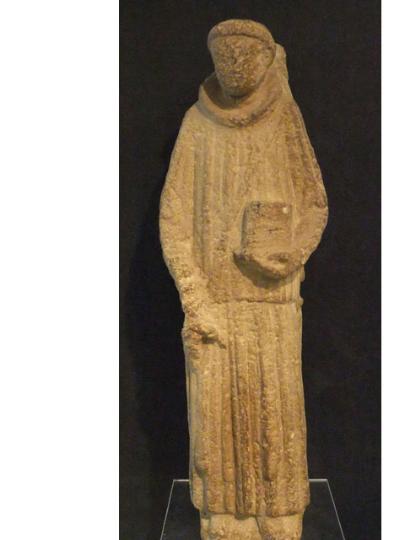

Self evidently the back of an oak carving, this is a twelfth century English full length figure of King Stephen. Known provenance leads to the expectation that this is from Furness Abbey in Cumbria which was founded by Stephen in 1123.

Rarity of such early English figure sculpture, most particularly of an identifiable person, verges on the non-existent. His deeply dried surface points to protective immuration for centuries.

He most worthily occupies pride of place on the Homepage.

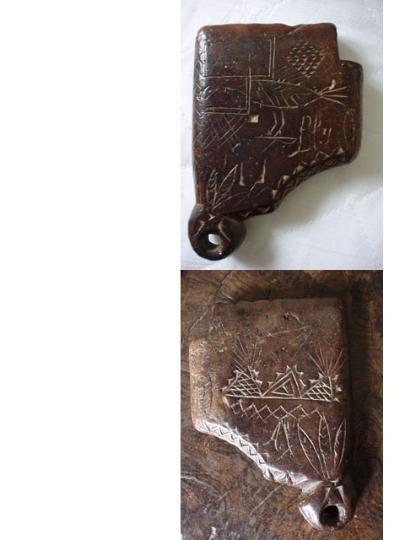

The 1 1/2 x 1 1/4 x 3/4" Lion is complete and in good order except for damage to its right lower leg, loss of the Candlestick-bearing figure of Henry, and extensive degradation of the gilding. Incised, highly symbolic decoration depicts Henry with his deceased brother William, many wild animals, and other images of functional objects. The Lion and its decoration were formed by a miniaturist who, despite their minutely small size, rendered the images so skillfully that they are identifiable by use of appropriately enlarged photographs or magnification.

The brothers William and Henry are depicted side-by-side : with facial features and distinguishing crowns enabling comparative recognition of each of them from period manuscript depictions. At William's right side is a letter 'W' that has the feathered end of an arrow projecting from it : this in allusion to the manner of his death. To his left is Henry, and to Henry's left is depicted a Fox : a rebus relating to his brother who by then already was known as 'William the Red' or 'William Rufus'.

Incised around the Lion are many images of animals. Henry later created the first zoo in the country by constructing a seven-mile long wall around the Royal Park at Woodstock, Blenheim, Oxfordshire : by which to constrain and retain the menagerie formed by his father William The Conqueror and continued by Henry's brother. That the Lion was decorated in allusion to the menagerie affirmed pride of ownership therein. Other non-anthropomorphic and non-zoomorphic images created on the Lion include a shield decorated with a Cross of St. George and a tripod-footed Cross of a design that appears otherwise unrecorded.

The Lion was recovered in 2019 from a field just South of the small, formerly Anglo-Saxon settlement of Thame, Oxfordshire. Rycote Palace in Thame was one of the many properties owned by Geoffrey de Mandeville : one of William The Conqueror's most respected and rewarded supporters who he had appointed 'Constable' of the Tower of London.

William 11 was shot to death with an arrow whilst hunting on 2nd. August 1100, and Henry ascended the Throne three days thereafter. Co-incidentally, it is recorded that Geoffrey died later in that same year. Much has been written about William's death and the succession : including the charge that Henry was complicit in the hunting accident experienced by his brother.

The form and decoration of the Lion shows it to have been of considerable commemorative and sentimental significance. Making the circumstantial but evidenced assumption that the Lion was commissioned by Henry as a memorial gift to Geoffrey, his father's close confidante, Henry might have been affirming his lack of complicity in William's death : their depiction together on the Lion inferentially proclaiming so. There is precedent for the depiction of lions (also of people) with their tongues extended. This being so with the Lion portrays neither aggression nor humour : but an invocation to avoid 'the sins of the tongue'. Henry might thereby have been decrying to Geoffrey the believing of rumour implicating Henry in his brother's death : and affirming innocence thereof.

Although of later date, there is at least one other reference to a king riding 'The King of Beasts' : from the mid-14th century Bohun Psalter showing Edward 111 so mounted.

Four other design characteristics of the Lion are of note. The practical and much-used handle, the stabilising base beneath the rear feet, and the vertical channel just forward of the saddle on the left side are confirmative that, when mounted, Henry was adjacent to a pricket candleholder that he was holding : there otherwise being no functional or aesthetic reason for these design features. There is a near-identical placement of a candleholder shown in the drawing of a 12th century mounted horse now in the Louvre. Positioning of the candleholder shows Henry to have been left-handed : this confirmed within a manuscript of the period showing Henry with nothing in his right hand but a sceptre in his left. Also, in either dry humour or mockery, the maker portrayed an image of himself (head only) in a position only now visible following loss of the figure of Henry. His impudence (and irreverence in context) in so doing was further enhanced as his tongue is sticking out.

Whilst two-dimensional images of Saint George slaying the Dragon are almost commonplace, an English medieval image in the round is a different matter.

The manner in which this 26" high oak figure is made shows that he was positioned in the true upper right register of the archivolt of a doorway.

The story of Saint George is handed down from third century Rome. It was not however until the late medieval period that he began to be depicted as in this composition as the Patron Saint of England slaying a dragon.

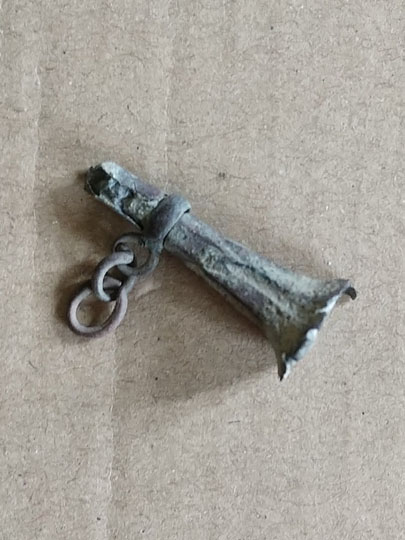

This is an iron, fifteenth century bifacial Maryan Guild processional image or sign which will, as indicated by the mounting tab, have been carried on a staff in procession or ( much more probably in view of the bullet hole complete with burning ) have been displayed as a sign outside a Guild Hall. The appearance suggests having been treated with a tarry preservative material which has now resulted in a compacted, very stable patinated surface.

It is known with certainty to have formerly been in the ownership ( collection of? ) Matthew Boulton ( 1728-1809 ) : the renowned metalworking industrialist and business partner of James Watt.

A fixed or portable sundial, of ancient origin, can be used to display the time of day by reference to the Sun. The essentially portable Nocturnal, when deployed in the northern hemisphere, enables determination, within a quarter of an hour, of the time of night : by sighting of the North Star and its positioning relative to other celestial bodies.

Made from fine copper alloy plate and approximately 1 1/4" x 1/8" this near-complete Nocturnal was recovered during a 'Detectorist's Rally' held close to Doncaster and is similar to the seven such recorded on the British Museum-managed Portable Antiquities Scheme database. Whilst there may well be others known, unlike as with sundials few appear to have survived. This tends to confirm that few were made during the medieval period as the earliest records of their existence are from only shortly before the Reformation.

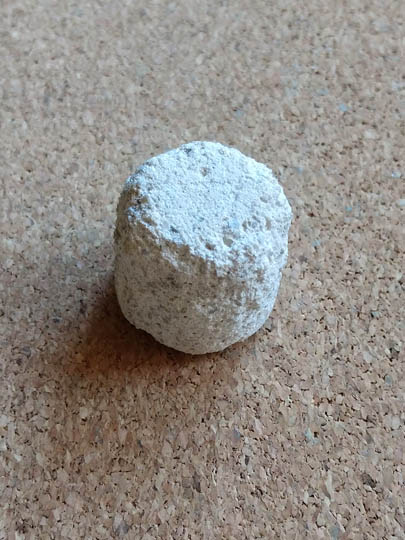

More easily recognised and understood than the Nocturnal on the previous page, the Sundial is clearly portable at its diameter of only 1 1/8" when excluding the 1/4" handle. Made from a small cast billet of lead, it has been wrought : except for the plain, flat back that utilised one unmodified face thereof.

Undamaged and in complete working order, it had limited functionality in enabling determination only of the canonical time of sext at midday.

There were monasteries close to Wentbridge in West Yorkshire from where the Sundial was excavated but, whilst its design confirms its monastic origin, it is not possible to determine the monastery from which its owner came.

Writing in the 1950's, Mackay Thomas first used the rather well coined phrase 'first stabilised English form' in order to codify this form of candlestick which we colloquially call the 'bunsen burner'.

At first sight there appear to be quite a few of these extant but, on eliminating both the vaguely similar French sticks and later reproductions and fakes, there really aren't many to be seen. Of those, all but four are made of copper alloy and there is one such in the Collection. The four which are not made of copper alloy are each made of tin alloy ( pewter ) : one in the Museum of London, the second with Stirling Castle Museum and two including this one in private collections.

With a height of 4.6" and diameter of 3", it is not only rare as a candlestick but also as a piece of English medieval pewter of any type.

As in the preceding page, this also is a bunsen burner type candlestick but made, more usually, of copper alloy ( bronze ). It is interesting to note that many fragments of stems and sockets of this type are available on the market which enable comparison with the relatively few surviving complete sticks. For reason(s ) difficult to deduce however, almost no bases of this type are found in isolation by archaeological investigation.

Despite the observation made on the previous page as to the relatively plentiful survival of Bunsen Burner type candlestick stems, apparently only two extant are in pewter : this being one of them. Whilst notable for reason of scarcity, this also is materially smaller at 2 1/8 x 1/2" (maximum) than other Bunsen Burner candlestick stems : showing the complete candlestick from which it originated also apparently to have been incomparably small.

Not only are Bunsen Burners considered to be specifically from England but, from the medieval period, manufacture from pewter and the absence of an aperture in the socket also is confirmatory of such origin. Perhaps academically controversial, upon handling aspects of its making strongly suggest that it dates from the Anglo-Saxon period.This should not be unexpected, as the general form can be seen not least in a surviving sixth century Norse wooden candlestick.

This was used to make wicks from the pith of rushes that then were enrobed in wax to make 'rush candles'. These are not to be confused with fast-burning 'rushlights' that were made from long rushes dipped into fat from cooking. Rushes used for making rushlights were dried and peeled of most of their outer stem : the pith and remaining supporting stem then being dipped into fat. When making wicks for rush candles, however, all of the outer stem was removed and a short section of pith fed between the rollers in order to consolidate/flatten it prior to enrobing with wax.

Made of copper alloy and measuring 1 1/8 x 5/8", it is in complete good order except that one roller now is not held securely in place.

In even the most modest of homes the production of rushlights will have been an extensive and lengthy routine family task. By contrast, the Wick Maker's small size and impracticability of use indicate that it will have been used briefly and infrequently for the making of rush candles. Whether this was a traditional form of tool is unknown : but perhaps is unlikely as no other examples appear to be recorded. This might be explained either by rush candles not being favoured or that devices as small as this one have gone unfound/unrecognised.

Acquired from the detectorist finder (who is to be commended for its safe finding/keeping complete with the 'loose' roller), this was recovered from West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire in October, 2019.

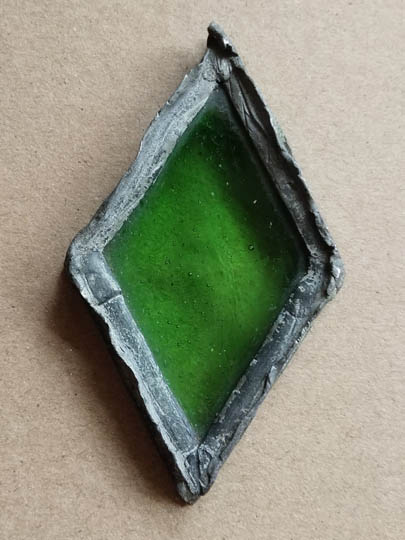

Different types of lantern, variously for use inside and outside, with their inherent protection against being extinguished by draughts or wind, were commonplace in the Medieval Period. This has not been reflected however in the survival of apparently only seven (including a Roman one) additional to this example : each being fragmentary and six of which are retained within museum collections. As a result of this dearth, knowledge of lanterns is derived mainly from extensive period depiction of them.

This example comprised two discrete elements : the base that is in complete, original good order, and the dome, now lost, that also was a complete entity. The base will, on occasion, have been used without the dome and, at other times, with that fitted into place by insertion of its six feet into the hexagonally positioned small apertures in the base. The aperture outside the footprint of the dome, of similar size to that which held the candle centrally, will have held either a lit candle used to light other candles, or one unlit kept in reserve for use within the Lantern.

The 3 1/2" diameter base (excluding the handle) has been fabricated in an apparently simple but actually highly workmanlike manner from three flat pieces of tin-rich pewter. If the cover had been designed to fit into or onto the base in any other way, that its six feet were each extensions of stanchions into which were slotted finely-shaved horn windows might not have gone unrecognised. However achieved within the design of the dome, whether or not by use of a lid, apertures enabled ventilation : and hence combustion. The handle was formed by bending a 3/4" wide strip of tin and upturning its sides to fit with finger and thumb. At its lower end the strip finishes in a tightly rolled hollow tube spanning the width of the handle and 1/8" in diameter. This held a taper (probably a short length of wick) that when lit possibly was used to enable passing of flame between the Lantern's 'external' candle and other candles. An original piece of this lighting material, clearly delineated from the tube, has solidified to remain evidentially in place.

The form of the Lantern in part bears comparison with that of one of the other extant seven : the impressively well conserved example in wood from the wreck of the Elizabethan vessel Mary Rose.

No more is known of the provenance than that the Lantern came from an English collection formed during the 1980's.

Of a traditional form, albeit infrequently found when English, the 17" high oak candle-bearing angel is from Devon. Fortunately, the dignity of the figure is undiminished by the absence of the long-gone candlestick : formerly held as though being presented.

There is an interesting matter to note concerning his present condition. Whilst a small amount of wax has been applied to the front ( prior to joining the Collection ), the back has been left unpolished. It could be said that this has enabled co-residence of idealism and pragmatism.

Respecting that they were devotional objects of significance to individuals and communities, it cannot be missed that the market has been awash in recent years with large, crude, often late-dated, repeatedly over-painted Continental wooden figures of Mary. This does not apply to all. Memory of a beautiful, large, 15th century Nottingham alabaster of Mary from fifteen years ago, and another Romanesque French Mary in oak, approximately contemporary with King Stephen on this Homepage, offered recently in Paris, provide reassuring exceptions.

Being late Romanesque circa 1300, made of copper alloy, hollow-backed and measuring 21/2"x1", this 'group' is far removed from such Continental examples. It is highly detailed with, for instance, each of the four hands and the (presumed) pomegranate being held by Christ the subject of considerable care in making.

By reason of size, it clearly is a personal, devotional object : or is it? The contemporary, extensive deposit of a 'concreted substance' attached to the back has it appearing to have been attached to some solid structure of stone or metal. During a number of different periods, to have been known to own such an image in England would have invited virulent opprobrium at the least.

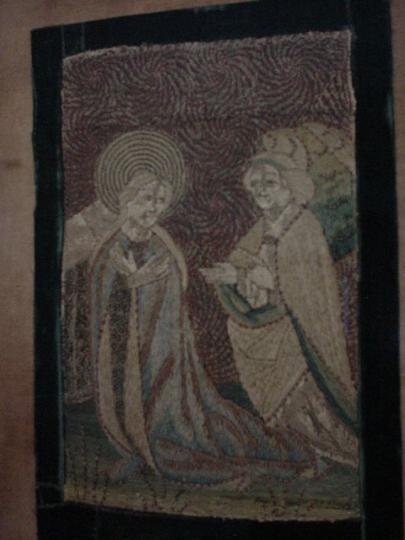

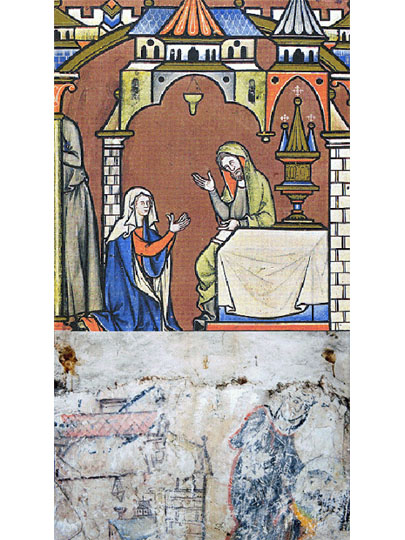

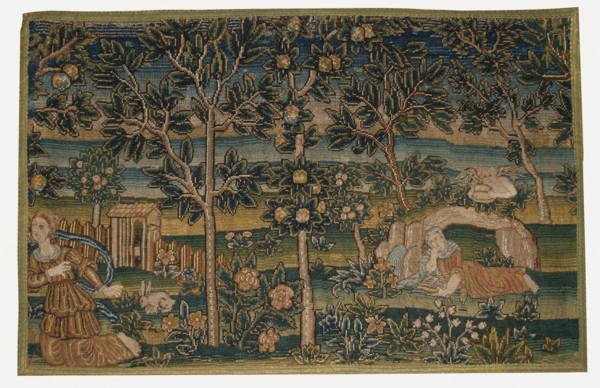

Apparently in the majestic Athelhampton House, Dorset until 1957, the subject of this late medieval needlework is that of the Angel Gabriel visiting Elizabeth to tell of the impending birth of her son John the Baptist.

What a contrast between this positive image and the many surviving gruesome depictions in both two and three-dimensional form of the head of John lying on a plate : by which this alone Herod's daughter Salome seems to be remembered.

Aquamanilia held water for the washing of hands : initially in ecclesiastical environments and later, more broadly, within wealthy society. Typically zoomorphic, but occasionally anthropomorphic, they were of such visual appeal and sufficiently durable that examples have survived in large numbers. As can be seen in the collections of a number of major museums, almost all are Continental and lack the aesthetic appeal of the 12th century English example in the British Museum. Many aquamanilia were lifted in order to pour water from the spout, but some were left standing : water being accessed from a tap protruding from the chest. Most probably, provision of such tap was in response to the effect upon the size and weight of the vessel at a larger capacity. Typically made of copper alloy and later, often highly attractively, of ceramic, it is known from period references that also some examples were made of silver, but none are known to have survived.

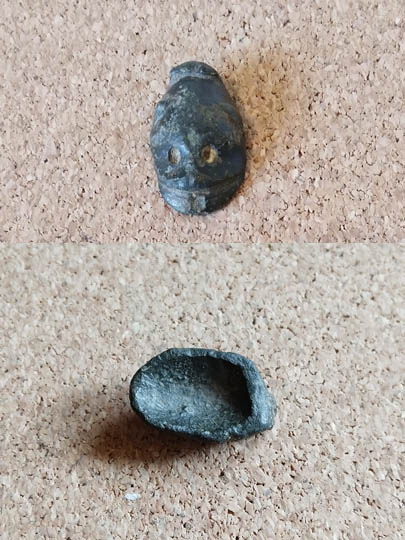

Recovered during the 1950s from Street End, Canterbury, and measuring 1 1/8" x 3/4", the Tap appears to be a sole English survivor : not just in silver, but in any material.

Increased wealth of a part of seventeenth century English society gave rise to ownership of much oak furniture of the day and this is still evidenced by the many extant exuberantly-decorated armed chairs. Earlier pre-Elizabethan chairs are both plainer and materially rarer and pre-Reformation chairs such as this are next to non-existent.

Unlike the other early chair from the Collection shown on a different page which required detailed description to enable understanding, this chair speaks for itself : excepting perhaps inviting just one question. Is its distinctive form designed for comfort or as a means of displaying the sitter? Whilst not uncomfortable, experience of it would favour the latter : not an unimportant matter to the furniture historian.

Horse Racing is today recognised as the 'Sport of Kings' but before and during the medieval period, Falconry held that position. Whilst disquiet may be felt at the wildlife implications, Falconry is rooted in the relationship between man and bird.

When not flying but prepared for such, the (say) Falcon is kept calm by having a hood placed over her head : the design of which is tailored for comfort and to enable easy placement and removal.

Hoods have traditionally been made of leather, and one of the two medieval examples in the collection of London's V&A Museum can be seen online to be made of leather which (reportedly) is very stiff : although unlikely so when made. By contrast, however, this (formerly) leather-lined, copper alloy, Helmeted Hood will always have been so and, whilst probably being made with care to fit precisely, will inevitably have accepted the compromises of display above comfort. The owner of the wearer clearly will have wished the apparel of his bird to match that of himself.

Measuring 1 3/8" x 7/8" x 1" and weighing one quarter of an ounce, the Hood was found in deep silt in 1976 (a year of extreme drought in England) at Stamford Bridge, Yorkshire (location of the battle in 1066 between King Harold of England and King Harald of Norway, days before Harold was defeated in Hastings by William the Conqueror). The late finder was a long-experienced dealer/collector of antiquities from whose extensive collection also has come one of the two Anglo-Saxon Page Markers in this Collection. An item dating from the eleventh century, as this has been seen to be, could be Anglo-Saxon, Viking or Norman but, based upon design, a cultural source has been nominated : albeit potentially open to revision.

When tethered inside, falcons stood on perches within a 'mews' : when outside, they were attached to a gauntleted hand or standing on a temporary perch. One form, an example of which is shown in a period depiction, was a small, round table top with a pole through its centre that formed both a leg and (above the top) a tethering post. When perching on the table top, the Falcon was tethered by connecting the short, thin, light leather straps (jesses) around her legs to the post or to a leash attached to the table leg or post. In either position, a ring of this type enabled a jess or leash to be wound around the ring's capstan : so tethering the Falcon with a greater or lesser degree of freedom to move as chosen by the falconer. When the ring was placed around the leg prior to it being inserted into the ground, by being constrained by the top and the ground the Falcon could not dislodge it. When however the ring was placed around the post, the intrusive positioning of the capstan on the ring rendered impracticable the raising and removal of it other than by accurate, vertical lifting.

Unlike any of the other few recorded tethering rings, this one is figurative and represents a serpent with the head of a ram : as depicted on other high-status artefacts in association with the figure of the Celtic God Cernunnos. The most notable example of this is shown around one of the greatest Celtic treasures : the Gundestrup Cauldron, that now is in the British Museum.

The traditional grouping together of the few rings of this type with the many strap-junction 'baldric rings' is, at best, uninformative. Whilst of elegant design and making, this method of tethering appears not to have been favoured with longevity : being only from the Celtic Period. Its demise might have resulted from conception of the so-called 'falconer's knot' : that could be tied with one hand.

Interest in determining the earliest date of Falconry in Britain led to theses on the subject : discovery/identification of related items such as this adding incrementally to that knowledge and record.

The Silver Vervel measures 1 x 1/2 x 1/4" and prioritises not burdening the bird in flight above durability : by it weighing only one eighth of an ounce. Used by a professional trainer, the Vervel was attached to a young bird by a fine cord around the leg that passed through the lower loop. A similarly fine leash was threaded through the loop at the top : so enabling restraint. Each bird was identified by the specific 'ring and dot' format on the shield. The seeming incongruity of the loops being offset from a central position enabled unencumbered close attachment to the leg. Following removal of the temporary Vervel just prior to later ownership, its functions were then met by the permanent fixing of a leg-encircling, owner-identifying Vervel Ring, and by the use of anklets around the legs for attachment of leather restraining Jesses. Whether this form of vervel typically was used during the early stages of training a bird during the Anglo-Saxon period might be determinable from the possible finding of other like examples or, less likely, from identifiable manuscript depictions of such.

During the period (and later), falconry was engaged in by those of high status and therefore became a well-resourced, high-value business. Experienced training of birds led to them being ascribed considerable monetary value. Distasteful though Falconry might be to some, its fostering of the relationship between bird and carer perhaps has merit in its own right.

This was found during the 1980s in Low Moor : some three-quarters of a mile from the dynastic de Lacy Family's Clitheroe Castle.

When attached to the leg of a falcon, the Vervel enabled both identification of the bird's owner and constraint of the bird : by placing the slot in a leather jess over and around the finial.

Cast and wrought from silver, the 1 1/8 x 1/2" Vervel is enamelled throughout in purple upon which is applied a lion rampant in gold : 'gold on purple' being a reversal of the 'purple on gold' of the traditional de Lacy Coat of Arms. Except for loss of part of the strap retainer on the back, partial loss of gold from the front, and the spurious green accretion, it is in good order.

The finial is formed as an image of the head of a dog. Interesting to note is the extent to which one side has been abraded by chafing of the attached jess.

Seven inches high and dating from the 14th/15th century, the ceramic jug is notable by reason of aesthetic appeal, condition and provenance. It's attendant paper label shows it to have been a part of the stock or collection of the now deceased authority Jonathan Horne. That label, with it's reference number and price, said ' 14th-15th. century Witham Essex '. In more recent times, the label which had become detached, was placed within the jug. On seeing the jug and wishing to see the label, a visiting authority on his subject ( not ceramics ), gently shook the inverted pot in order to extract the label. Two labels fell out : the second being made of linen and filthy. In spidery inked writing it says ' Jug. found in digging Cellar. High Street Witham 1820 '. The finding of the label was nearly as exciting as the original acquisition of the jug.

5 1/2" in height and 7 3/4" in maximum width, the Vessel is unrestored and undamaged, except for minor chips in the rim. The depression in the rim adjacent to the top of the handle is a thumb hold that, with the second forefinger around the handle, enables lifting and tilting to drink from the lips to both left and right of the handle respectively, by left- and right-handed users.

Whilst undoubtedly made for communal use, the Vessel would not have withstood other than careful handling. This therefore would preclude 'on-demand' use by the public : say when in a tavern.

Excavated from Warwick in the 1940's, when private domestic use is precluded, there seem to be few environments and locations from which the Vessel might have originated. Its lowly status probably excludes buildings such as Warwick Castle : or even typical manor houses. To suggest likely sources in Warwick from which such a distinctive vessel for use by a small confraternity might have originated would not be difficult : but would be unacceptably speculative if unprovenanced.

The Mute Swan is mysterious and beautiful, creating in its graceful passage an aura of serenity and calm : unless and until it is annoyed. Now held in unwavering regard, it is interesting to know the reasons why that was so also in the medieval period.

Following two complete vessels in preceding pages, a handle alone apparently makes for poor company : until the status of medieval swans and those associated with them is taken into account. The handle is made of tin alloy and measures 21/4" in length with a maximum width of 3/4". The attachment end is hollow for less than 1/2" and therefore dispels any though of it being a spout. The jug/cruet of which it was the handle clearly will have only been small in size and capacity.

There was rigorous control of ownership and keeping of Mute Swans both during and following the medieval period. This emanated from the Kings of the day who dictated which few organisations and wealthy aristocrats were granted permission to own Swans. This regime was controlled by expensive licensing and formal marking of each Swan. Strictly enforced law dictated the conduct of those not allowed to own Swans even down to not allowing their removal from land being occupied and grazed by them. All of this will have added to the mystique, aura and status of the Swan and, even nowadays, it is thought ( albeit incorrectly ) that they are all owned by the Monarch. The present-day ceremony of 'Swan-upping' involving the capture, marking and release of Swans in the ownership of the Crown and specific livery companies is in continuance of practise from the medieval period.

Whilst there are both livery and other badges depicting Swans, there seem to be very few medieval examples of them in three-dimensional form. This may have resulted from their near-sacrosanct status. Conversely, those with such objects in their ownership may thereby have displayed their standing in Society based upon their involvement in any capacity with Swans.

Whilst not conveyed to good effect by the picture, the shaping of the handle would readily enable pouring to the left rather than tilting backwards, when held between the right thumb and index finger : indicating that the handle was more likely attached to a jug/cruet rather than to a drinking vessel. Such a small vessel would likely have been an ecclesiastical cruet were it not for the zoomorphic design of the handle. Realistically however, the circumstance of its use is a moot point : retaining all the mystery of a Mute Swan.

So different to the remote, isolated locations of many major English monasteries, St. Mary's Abbey was established in central York by the Benedictine monastic Order. Dedicated to Saint Olaf of Norway on its foundation in 1055, it was re-dedicated to the Virgin Mary in 1088.

Two and a quarter inches high and made of copper alloy formerly gilded, the Pendant was excavated in the 1950's during a formal archaeological investigation of the gardens adjacent to the remains of the Abbey Church : themselves the site of other elements of the monastic complex.

The obverse depicts a full length image of Saint Olaf : the Viking King sanctified in recognition of his role in the spread of Christianity. Olaf died in battle in 1030, and his faithful witness inspired dedication of the Abbey in what was the capital of Viking-controlled England : the Danegeld. Some aspects of the detail remaining have enabled correlation with extant period statues and pictures of Olaf. Note that, whilst adjacent to slight damage, there remains an identifiable Cross to his right. Also, at his feet, is a swan leading him in the manner of a 'Knight of the Swan'.

On the reverse is depicted the 'Sacred Heart of Jesus': the iconographic form of which was first introduced into Cistercian and Benedictine monasteries by returnees from the Crusades. Above the Heart is the Crown of Thorns from which flames are engulfing a Latin Cross : thereby conveying Christ's sacrifice, divinity and love of mankind. By the Cross being consumed by flames and materially smaller than the Heart, in contrast to the relative size of Christ and the Cross as typically depicted in the Crucifixion, Christ's love is shown to have conquered all.

Clearly a devotional Pendant for wearing, whilst only a part of the attachment loop remains, it otherwise is almost undamaged and in uncleaned, stable, long-lasting condition.

Found at the same time in the 1950's as the Pendant on the previous page, this is a complete hand Tool made of copper alloy, measuring 1 3/4" x 5/8", with traces of green, red, and black ink/paint and in original good order. It was used by monks in order to compress parchment when folded to form bifolia : that thence were bound into books. Also, to finely dress those parchment pages, when necessary, prior to or during writing. Whilst the Parchmenter will have selected, stretched, dried and dressed skins for use as manuscript pages, monks engaged in their use will inevitably have found the need to engage in further, limited preparation. Whether or not by use of very finely-grained materials, blemishes will have been filled and smoothed into a state acceptable for use. It is interesting to note that stones thought to have been used for the purpose have been found in an English monastic site : although the finding of a tool such as this perhaps suggests that those stones were used only in the early stages of skin preparation.

The ease with which the thumb and forefinger fit aside the curves between stem and smoothing plate enables the application of controlled, highly effective pressure to compress thick pages along their folds. When used to dress pages with smoothing substances, this has the feel of a delicate trowel capable of accurately careful use.

Addendum

A second Parchment Tool, of identical design but approximately half as large again, has been acquired from the finder : it having been recovered from adjacent to the former-Roman Fosse Way, Cotgrave, Nottinghamshire. Providing yet further evidence of the nature of its use, this also, in good original condition, has identical spots of red, green and black paint remaining on its surface.

Sliders were used during the activity of copying manuscripts by hand : this being the only means of replicating written material during the medieval period. How widespread was their use is a matter of conjecture.

Recovered with the items on the two previous pages, the Slider, finely made of tin alloy, measures 3/4" x 1/2" x 3/8" and is in complete, good order. Threaded by two tactile cords and laid down the central fold of a book that was being copied, it was slid, by use of the two finger-holds, down (and sometimes up) the cords in order to denote the line then being copied. Evidence of the efficacy of using a slider can be seen in the occurrence of inadvertent repetition of lines in some extant manuscripts. Whilst the back is decorated with a rose that references the Virgin Mary, and hence this owning Monastery, the front reflects typical Anglo-Saxon humour by depicting drops of ink.

Whilst other sliders appear not to have survived, one that is functionally similar but different in design is depicted at the top and in the centre of a page in an extant manuscript. The correlation between the design and function of this Slider is so confirmatory of use that, whilst that manuscript is interesting to see, no reference to another slider is needed to support attribution of this one.

Once again, here is a fractional part of the academic legacy of the archaeologist, the late Gordon Hardcastle.

Most modern coinage has effectively no intrinsic value, but that was not so during the medieval period. The predominant English coin was the silver penny : the standard weight of which was uniform during long periods of time but changed at certain, known dates. Being made of silver, pennies were ripe for 'clipping', and someone receiving payment had good cause to ascertain that they were of full, standard weight.

To gauge the weight of objects larger than, say, pennies will have been undertaken by use of a scale with separate weights of specific, different values. Being small, light and of specific, standard weight, pennies enabled development, making and use of a portable device specifically and solely for weighing them : that device was the Tumbrel.

Found in Lancashire, made of copper alloy and measuring 2 1/2"x 3/8" x 1/4", this is one of quite a few survivors from the period. It is, however, notable by reason of its completeness, original condition, fine surface decoration and overall making in the form of a hound. The Tumbrel was opened in 'scissor-like' fashion and held so that the balance arm was horizontal. The coin was placed on the plate at one end of the arm and, because the opposite end of that arm was made of the appropriate, specific weight, the coin would either remain on or 'fall' from the plate. Only if falling would the penny have been determined to be of acceptable weight.

Despite 'dress accessories' not being acquired for the Collection, an exception was made for this monastic item of known provenance.

Many purse bars have survived : now devoid of the fabric bag which encased them. By contrast, the means by which they were suspended from belts either have not survived in numbers or have gone unrecognised as to their identity.

This Monastic Purse Hanger is made of copper alloy, in complete good order and measures 2 1/4" in length and 3/4" maximum in width. Found in Lewknor, Oxfordshire, the location of the Benedictine Abingdon Abbey, it is probable that this was the personal possession of a 12th or 13th century monk. The attachment clip that slotted down the height of his belt is almost as long as the figure itself but appears not to have saved its loss following detachment. One unusual feature of the figure to note is the one, large foot : crudely and plainly made, it appears to have been without the accompanying right foot since being made. This bare foot may have been modelled in order to evidence ascetic penitence : despite its use to suspend a purse.

The copper-alloy Lamp measures 3 3/4 x 3 1/2" excluding handle, has an aperture of 1 3/4" and weighs 2 lbs. 4 ozs. Aspects of its design, condition, and provenance enable certain attribution of its function and probable attribution of its original source. Although external surfaces evidence little exposure to heat, the inside is heavily encrusted with heat-bonded material. Following being filled with shards of cold, hard beeswax, it was suspended over boiling water to induce melting and consolidated filling of the cavity, including the lip. With red colourant stirred into the molten wax, and a wick inserted into that, it was left to cool and set. Deposits of ancient colouring remain : integrated with, and on the surface of, the remaining wax within. It is noted that, although probably here not applicable, particles of silver can, following contact with acids (e.g. from the ground), produce traces that are coloured red. Its tripod form and very heavy construction strongly suggest that originally it was used within a rugged environment : not that of a genteel, protective building. Neither of these characteristics would have been needed it it had been displayed on the flat top of an Altar or piece of furniture.

The Lamp was recovered circa 2000 from the ground within 100 yards from the now disused Chapel of Sainte Antoine de Froidemont that was established in the small village of Plancher-les-Mines : the location of the most prolific silver mine in the former French Empire. Sainte Antoine, Patron Saint of Miners, was a 9th/10th century monk from the Benedictine Abbey of Luxeuil who, in his later years, moved to a hermitage cave in the large forest 2 1/2 miles from Plancher-les-Mines. Both that forest, hermitage, local waterfalls, and the Chapel bear his name. Recognising the ecclesiastical nature of the Lamp, that it postdates Antoine's hermitage and that it lengthily predates the original 1745 village Church, its 1868 successor, and the Saint's Chapel of 1866, to attribute it to have been in a typically French Shrine to Antoine within or adjacent to the silver mine that was (and is) close to the village, is not without foundation or justification. As found so close to the Chapel, it seems probable that this had been used and/or displayed therein following transfer from the mine but subsequently buried in haste to ensure its safety from anti-Catholic attack. Ownership and control of this area of France moved more than once between France and Germany during the period post-1866. As a result, virulent German anti-Catholic sentiment was, for a period, enshrined in law, and such a Lamp would have been a prime target for despoilation. Burial for safe-keeping, subsequent finding, and now identification, have defeated the iconoclasts.

Throughout most of the medieval period, men displayed their affinity to people or organisations by the wearing of a Collar made of precious metals. In effect, a medieval Collar can be equated to a current-day necklace : albeit on a very large and grand scale. From the Collar typically was suspended, in a central position, one decorative item which further reinforced the wearer's affinity. Collars also can be well visualised as period equivalents of Chains of Office. Well remembered is travelling on Concorde from London to Berlin in the only small party which could be carried in such splendour : being led by the Lord Mayor of London ( holder of the twelfth century office and not that of the Mayor of London which is a recent foundation for administrative management ). He was wearing 'The Jewel' suspended from a fabric collar around his neck : this being the 'everyday' insignia worn in representation of the full Chain of Office. The Jewel corresponds to those of various forms suspended from medieval Collars as described. Of course, the Niche is very modest by comparison and it is admitted that schooling at the time was required in order to learn of the Mayor's apparel : this coming from a brave former MP ( with an even braver wife ) who deserves to be held in high national esteem.

Made of gilded silver, this is in the form of a niche with a looped attachment on the back enabling recognition of its means of suspension from the Collar. Fortunately still in unrestored good condition, it measures 11/4x1/2x1/4". Obvious however, is the absence of the figure which will have been reverently presented within it : most probably of Mary. This is a mixed blessing for, if the ivory figure had still been present, it would not have been acquired for the Collection by reason of love of and respect for the Elephant.

Such angels were ( and still are ) positioned vertically or at 45 degrees within the roofs of ecclesiastical buildings. This fifteenth century oak carving is 3' high and has, presumably at the Reformation, been subjected to what can most accurately be described as a sustained attack with an axe. We can only despair at the anarchistic ideology which resulted in defacement and desecration of such a figure of humility. Sad to say, the angel provides a more effective historical record than would be the case if free of such treatment. In present hands, it also is considered more empathetic than if it had been left in peace : comfortingly so.

There are a good number of surviving fragments of this type of English fifteenth century copper alloy folding candlestick. However it is not surprising, considering the fragility of the design and manufacture, that there are very few which are as complete as this one. An example of such is in the Museum of London.

The stick could be inserted vertically or horizontally into an aperture : in either position, being secured by the locking mechanism. When not in use, it could be folded as though a pair of scissors such that both the socket and spike were adjacent and pointing in the same direction.

It is notable that this is one of very few different types of English medieval candlestick extant.

Whilst apparently a simple, minimalist means of positioning a candle for use in lighting, the attention to detail in the design and making of the Stand reveal it to be anything but modest. It was found in 1975/6 by a professional archaeologist working in Newton Kyme, Tadcaster, North Yorkshire : the site of a major Roman Fort subsequently occupied by Anglo-Saxons.

Measuring 1 1/8" x 3/8" and weighing an extraordinarily heavy 1 1/8 ounces, it is turned and carved from extremely dense Tadcaster limestone : as used in the Minster and City Walls of nearby York. With a flat bottom, vertical and chamfered sides, and incised, dished top with rolled edges, it clearly was produced by a skilled mason.

Following lighting a candle stub positioned on the Stand, hot wax would have been dripped into the dish, and the candle re-positioned thereon to ensure stability. Beyond all reasonable, optimistic expectation, and despite previous unawareness both of this and of the functional identity of the Stand, period wax deposits remain in the bowl.

Whilst a simpler form of lighting (other than firelight) could hardly have been conceived, the care taken in its conception and making is indicative of its significance to the owner : and of the Anglo-Saxons' approach to making mundane objects.

Irrespective of intrinsic value, the most prized possession of a monastic or other ecclesiastical community was the chalice : it being central to the celebration of the Mass. With the exception when license was granted to specific institutions in times of exceptional penury, medieval church law forbade use of vessels made of non-precious metals in such Celebration. This thirteenth century chalice is made of tin alloy : that is to say pewter. With some notable exceptions in respect of senior members of the Priesthood, the practice of burying a representative chalice and paten with a priest was satisfied with vessels made of pewter and not of precious metals. Most fortunately, this chalice was found in 1908 at Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire during the construction of a croquet lawn.

For reason both that it is a chalice and that it is probably the only funerary item in the Collection, it receives all due care and respect : objects are infused with their history.

Chalices and Patens buried with priests other than of high status were piously simple in design and making : being representative of but clearly identifiable as to function. Predominantly by having been excavated from ecclesiastical environments, chalices have survived in sizeable numbers : but seemingly inexplicably, patens materially less so.

This Paten is notable not just for its survival but for its design and manner of making. With a diameter of 1 5/8" and made of tin alloy, so untypically nominal is its design it merely alludes to being bowl-shaped by the incising of the upper surface : being scored both to delineate the booge and around the rim.

Emblematic of the many thousands of objects excavated and collected by the archaeologist Gordon Hardcastle, the Paten was recovered in May, 1975 from the field immediately behind All Hallows Church in Sutton-on-the-Forest, North Yorkshire. The Church was rebuilt in 1876 incorporating elements from its early fifteenth century predecessor, on the site of its yet earlier predecessor that dated from 1185 at the latest. There then being effective ownership of the Church by nearby Marton Priory, that uniquely was a double-house of Augustinian Canons and Benedictine Nuns, it is likely that the Paten was buried with a Canon from Marton : each Canon being a priest and therefore buried with Chalice and Paten.

Unlike the Paten on the previous page, this one was intended for use and not for burial with a priest. The Pyx of which it was the Lid contained the Reserved Host for celebration of Mass with those in distress and the Lid also served as a Paten upon which to place the Host during that Mass.

Made of a roundel of thin tin alloy with a diameter of 2 1/16", the outer 1/16" was trimmed to leave only the small V-shaped handle to protrude : by which the close-fitting Lid Paten was raised from the Pyx. The remaining outer rim was then hammered over a former in order to produce a concave lip to fit over the matching convex lip of the Pyx. The minute handle projected out from the lip of the Pyx and then turned down at 45 degrees. Together with the incised decoration, the quality of material and making are consistent with its function and high status.

Coming from the collection of a detectorist from Felixstowe, Suffolk, it is likely to have originated from Felixstowe Priory.

As seen by some scholars invested in the subject, the solution to Riddle 48 in the tenth century Anglo-Saxon 'Exeter Book' is 'Paten'. There alluded to, in a manner typically used in Riddles, is the writing of a religious text onto a paten, the subsequent washing of the paten with consecrated water, the recovery of that water together with the ink used during writing, the saying of prayers over that water and the provision of it to be sipped by the person in distress with whom the Mass was being celebrated. Notable is that this Pyx was used in serving the distressed : increasing its significance within the context of that similar circumstance alluded to by the Riddle. If the Pyx had been used more generally, there would have been a lesser correlation between it and that alluded to in the Riddle. As Anglo-Saxon decoration typically was meaningful, interpretation of the decoration chased into the upper surface might lead to greater understanding of Riddle 48.

The Paten at present appears to be a sole survivor from the period.

Whilst medieval ecclesiastical patens (and chalices) have been published in informative detail, it appears that no others remain that identifiably are from the Anglo-Norman period.

Made from a 4" diameter thin roundel of gold that was beaten over a former to create the lip, it then was heavily gilded on all surfaces and, during cooling, a circular mould placed on top in order to impress the text. Following cooling, the then raised areas surrounding the text were stippled by use of two tools of different sizes. As a result, the text was delineated by the raised area around each letter and not by the letters themselves. The concave lip around the rim ensured that the Paten fitted closely over the Chalice in lid-like manner and did not overhang it as was the norm during the later Medieval Period. That a chalice and paten together were simply called a 'chalice' in early references might reflect this earlier, more intimate, physical format.

At centre-left is one of the traditional forms of Christogram : an image of the numeral 4 depicted horizontally that represents an abbreviation of the name 'Jesus'. Then the first word of the text that formerly encircled the complete Paten is PENSE (consider that). Interpretation of the final part of the text that is to the left of the Christogram, is less certain. The letters 'IS' might be for either 'Jesus Saves' or just the name 'Jesus'. In the alternative, the apparent letter 'I' to the left of 'IS', together with the 'I' of 'IS', formed a different letter. If so, that letter and the 'S' that followed it would be the last two letters of the final word of the text now lost. In the widest interpretation, possible contenders for that ending are AS, HS, MS and NS.

Acquired from the finder, the Paten was excavated between 1981 and 1985 from the Billingsgate Wharf on the Thames that is immediately adjacent to The Tower of London and very close to the church of All-Hallows-by-the-Tower : the first church in the City established prior to 675 by outreach from Barking Abbey. Postulation that the Paten originated from the Church or one of the two chapels in the Tower of London has merit. Least likely is that it came from the Saint John the Evangelist Chapel in the White Tower : it being of high status but falling short of the standard we perhaps would expect to have been used during serving the King privately. The Chapel of Saint Peter ad Vincula, that now is situated within the Inner Ward of the Tower, served the apparent 1,000 people who worked within the Tower. Whilst it is a matter of conjecture, perhaps the use of Anglo-Norman French text evidences conformity following the Conquest that might suggest Saint Peter's rather than All-Hallows as the source of the Paten.

Found at the same time as the Funerary Paten on the previous page but two, this also probably came from either the original, early church at Sutton-on-the-Forest, North Yorkshire or from Marton Priory.

1 1/2" high, 1" wide and made of copper alloy, the Candlestick is in the form of a pair of leaves placed back-to-back : leaves representing hope, renewal and revival. Although appearing unlikely, it free-stands securely and will have been placed, with candles lit, before an image of the Virgin Mary : hence not left unattended. Also appearing most unlikely, it can be held securely between thumb and finger.

Complete but for the upper third of one socket, paired lights represented to the Church the duality of Christ as God and man. Its monastic function, design, and particularly the narrowness of the sockets indicate that short, hybrid, beeswax-enrobed rush candles probably were used : rather than conventionally-wicked candles.

Despite the absence of the vessel within the rebated lip of which this sat, its shape, size and ecclesiastical decoration are confirmatory of it being the Lid of a Pyx that was used to contain the Reserved Host : as referred to on the previous page.

Finely made of copper alloy, with a diameter of 1 1/4" and a height of 3/8", it has come from the collection of a detectorist from Thetford, Norfolk. Whilst conjectural that it originated from the Cluniac Priory of Our Lady of Thetford, its characteristics are consistent with attribution to a monastery of such standing. The Lid is decorated with four lobes forming a Cross : surmounting which the handle is formed as a Cross Pommee. The pin by which the handle is attached to the Lid is complete and extending only to be flush with the underside of the Lid : thereby confirming that it was not attached to a lower lid of greater diameter as might have been supposed.

Whilst many enamelled pyxes from Limoges have survived, there are very few remaining that are English : to the extent of increasing the significance of this Lid.

Made of gilded copper alloy and at lengths of 2 1/2" and 2 7/8", although closely similar, the Spoons were not recovered together.

The ends of each Spoon served different, but related, functional purposes : the cup being for anointing with consecrated oil and the bowl for serving the consecrated mixed water and wine to the recipient of Mass. Their design and small scale assert their dedicated function in providing succour to the sick or dying : reflecting use of the generic term 'travelling spoon'.

Although the geographic source of the smaller Spoon is not known, the larger one was acquired from the collection of the finder. Recovered during the 1970's, with commendable frankness at his uncertainty, the supplier explained that it probably was one of many items then recovered from Hertfordshire. These being similar but not identical, such Spoons invite the thought that there was then a typical form : of which other examples may be known/found.

This English fifteenth century sandstone carving is about 11"x11"x7" and depicts the known form of a 'cautious man'.

A notable aspect of his provenance is that the true pair to him depicting an 'incautious man' was sold at auction in recent years : whence described as a 'Green Man'.

The seemingly complex shaping of this piece of ceramic misinforms as to the simplicity of its design, making and use : the two indentations being merely thumbprints into the clay used for its manufacture.

Measuring 1 3/4" x 1 3/4" x 1", it is complete as made and has sustained only limited surface degradation : in the form of cracking along the tracks for/of the wicks.

Small pieces of solid beeswax will have been placed in the two apertures and the whole heated sufficiently to enable controlled insertion of wicks into the molten wax : each overhanging the upper lip. Following cooling and hardening, one or both wicks were lit according to need.

Recovery from the River Tees at Piercebridge, County Durham in 1976 most likely was facilitated by the extreme drought that year.

So essential and extensive the need for lighting that the variety of solutions devised to meet it should not surprise. This is perhaps one of many the purpose of which has gone unrecognised.

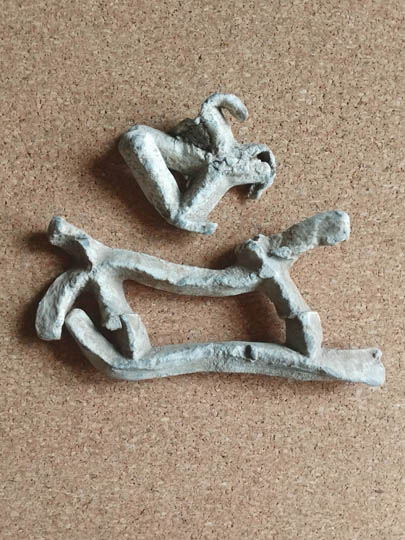

With such an interesting and unusual subject, usual antipathy towards anything from the mass of available material called 'mounts' was suppressed in order to have Adam and Eve join the Collection.

Made of copper alloy and measuring 1"x11/3", self-evidently it is pierced and deeply modelled so as to transcend its small size as seen.

There is just one other known which is nearly identical and recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. That was found in Hampshire and dated 1100-1300. If only the one from the Collection had been known at the time of the PAS listing, that they represent Adam and Eve aside the Tree of Life and are next to certainly box mounts would have been recognised and recorded: mounting pins present being of a scale indicating a box and not a belt mount.

We have reason to be grateful to those whose research of early things has been recorded for posterity. The subject of processional crosses and the figures attached to them has received studious care from a number of such academics.

In a sense, without cheapening these, they can fairly be described as formulaic in design and making. Made of gilded copper alloy with figures of Christ in the centre, the Virgin Mary to his right and Saint John to his left, even the moulding of the bases as attached to the overall structure of the cross is to a common pattern. This is not to say that there are many figures surviving : those which did will have been broken from crosses at the Reformation to be retained by the faithful as devotional images.

Whilst this 4" high fifteenth century figure of John is from an unknown location, fortunately the 'finding provenance' of the following three images is known.

From Castle Hedingham in Essex, this 31/4" high copper alloy ( bronze ) processional cross figure of Saint John is virtually identical to another in Colchester Museum.

( see preceding page )

Probably by reason of there being lead in the alloy used for manufacture, this 31/4" high processional cross figure of John from Runhall, Suffolk is materially heavier than the other figures in the group.

( see preceding two pages )

Whilst there are quite a few processional cross figures of St. John extant, those of Mary are near to non-existent. Perhaps this is because it will have been more life-endangering to have been found in possession of a Mary rather than a John during the Reformation period and these may well have been melted down in greater numbers. This 31/2" high figure is from Hindringham, Norfolk.

In order to protect the holy water contained in a medieval font from theft and subsequent profane use, a cover was locked into place. These substantial covers could sometimes reach literally yards above the font and be worked in considerable decorative detail.

Large covers were raised by use of a rope and pulley attached to a ( possibly roof ) beam. The girth of the ring for the rope would suggest that the associated cover was itself large and heavy : albeit not of the scale of some surviving covers. Perhaps now, it is most notable for its ambiguous blending of sternness and humour : the cherubic angel raising a supposed font cover which will have been matched in design by the actual font cover beneath.

Not every day is found a 'new' design of candlestick and, even less likely, a functionally different type of stick. Whilst this meets each of those criteria, tomorrow may be found a dozen like it.

Made of copper alloy and measuring 31/2" in height and a maximum of 3/4" in width, when inverted it looks to be a somewhat commonplace finial. Apart from the 'feel' of it when handled, three physical aspects do however confirm it to be a candlestick : it comprises two elements peened together in traditional candlestick-making manner if not form, the socket has been burned extensively over a long period of time and it even has compacted wax of years in that socket.

Whilst it will not have been unusual in a secular or ecclesiastical environment for a lit candle in one candlestick to have been used to light candles in other candlesticks, at the least it would have been an awkward and inelegant task. Medieval candlesticks made and used specifically for that purpose appear not to have been identified or discussed.

Being overtly Roman in style and hence somewhat alien within a Medieval Collection, this 'dual-aspect' candlestick is considered relevant for inclusion by reason of its functional purpose. Whereas the candlestick shown on the previous page was most likely used for lighting other candles, this was used for spacial lighting when being carried : with the wide or narrow socket in use depending upon circumstances.

Measuring 3 1/2" in length and with external socket widths of 1" and 1/2", it is made of copper alloy and in good, complete condition. So straightforwardly basic a form as this invites calling it 'a Torch' and it would not be surprising if this were to accord with Roman nomenclature therefor.

Similar in basic form to the candlesticks on the two preceding pages, it is by reason of the fabrics, surfaces and decoration that such different periods of making can be ascribed to each one.

Measuring 1 3/4" in length and with a maximum socket width of 1/2", this is made of copper alloy with the only 'period-indicating' decoration being that of the vertical striations which surround the socket.

This is a somewhat unusual object from the period : which seems now to be represented mainly by extant weaponry, tools and items of personal adornment.

Whilst not visible in the photograph, there is a 'wire' straddling the aperture of the socket about 1/4" below the lip. When a tranversing knife-cut was made centrally across the base of the candle prior to it being pressed into the socket, this will have added considerably to stability of the candle when being carried. The fixing, if not the making, of that support, will have required skill and care.

Unfortunately, the only available provenance is that of it having been acquired from a British collection formed between the 1960's and 1990's.

Perhaps only by seeing depictions in manuscripts or tapestries may we learn the manner in which tables such as this were used. With an undecorated, single planked rear 'frieze' panel, it most probably was placed against a wall and not used for dining on any scale : other perhaps than for the well-understood practise of storing food and drink for the long evening candle-lit hours of darkness. The quite different form of furniture apparently most often used for that purpose, the buffet, is however well explored in the record.

The 5' 2" long oak table dating from about 1480 is English and mostly complete : excepting the 'cupboard' floor and re-tipped legs. There is another in the V&A which is somewhat less complete : apparently having only four panels and two front legs which are original. With respect towards the V&A's present curatorial staff, that this is described as a table clearly would not accord with current practise. The shaped and moulded legs and rails together with the carving of panels and door provide a quietly appealing, restrained aesthetic combination worthy of the period.

Retained with the Collection is a V&A postcard depicting their table which has the handwritten date of '21.11.40'. Whoever visited the Museum and bought the subsequently unposted card on such a dark day in wartime Britain must have been a serious enthusiast. Long may we maintain such interest in and commitment towards our shared heritage.

The role and function of reliquaries are ideally understood as an element of the cult of saints in the Anglo-Saxon and medieval church. The veneration of notable holy people took physical form in the creation of shrines to them, both within structures dedicated for the purpose and within ecclesiastical buildings for wider religious use.

Ranging in size from small, box-like reliquaries to 'body-containing-sized' tomb chests, they served the same purpose of preserving and presenting the remains, relics and attributes of the saint venerated at each particular location.

Some large structures, including tomb chests, remain in English churches. Also, by reason of the extent to which they were made and their aesthetic attractiveness, quite a few reliquaries from Limoges are extant. To reference an English medieval miniature reliquary however is difficult if not impossible: with the possible exception of one in alabaster in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Measuring only 11/4" wide, 1" high and 3/4" deep, the tin alloy reliquary is flat-backed, stands on lions as front supports and has a decorated front 'panel' with a true left hand panel in two reserves: each of which has a quatrefoil within it. It is complete except that the central section of the true right hand upper end has been broken away and that, as there is a slightly raised section at the top of the left hand end which is fractured, there may have been a low 'superstructure' of some sort: perhaps even a very low 'canopy'.

If this was one of many such, it would be seen to be a more complex ( three-dimensional ) devotional object but serving the same purpose as a pilgrim badge : that is, a memento of a visit to a particular shrine. Apparently unique, and thereby invalidating such explanation, it has, for the present at least, to be considered simply as a generic English devotional object.

Clearly depicting a young boy, this fifteenth century 15" high oak figure affords little certainty as to his role. Most probably ecclesiastical, he may be a member of a 'song school' : a chorister in the making. Perhaps less likely, he may be a young mourner or pilgrim. Notable, self-evidently, is his period dress and the extent of remaining original paint.

Acknowledging but discounting the many sometimes only vaguely similar Continental examples in brass, which often are anthropomorphic and usually post-medieval, this recognised form of English Candlestick has survived in even smaller numbers than those of the 'first stabilised English form' : two examples of which are shown on other pages. A pessimistic interpretation would say that only two of this Double-Socket form in a complete state are extant and that even one of those is questionably 'real'. The fully credible one deserving of being referenced is in the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, and can be seen online. Thanks to the sterling service provided by the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme database, it can be seen that there are approximately twenty fragments of this type of candlestick that have been found in England. Whilst the twenty include both sockets and fragments of arms of this type of Candlestick , just one is not only as complete as that in the Collection but, whilst also now having only one socket, still has in place the ring that held the second socket. In consequence of such limited survival, this one is of notable academic significance as a source of reference : its incompleteness being inconsequential for understanding.

Originally it will have comprised a tall, narrowing pricket peened into a round, unfooted base and a double-socket arm that was placed over and around that pricket to be retained in mid-position as it widened. Now gone are both the pricket with base and one socket with its means of attachment to the Arm. Made of copper alloy, the Candlestick will have been 3 1/4" wide and of indeterminate height.

Its finding on the boundary of the parishes of Fundenhall and Ashwellthorpe, Norfolk on 23.3.19 has enabled realisation of a long-held wish to have an English example of this form in the Collection.

One of only four English medieval credence tables extant, this was inset slightly into a chancel wall and pinned thereto by brackets the apertures for which are present and undisturbed in the back of the table. Mounting brackets in similar form to the period ones have been made to hold the table in place on an oak stand and hence to display it as when originally installed.

Much has been written on the function of such tables but, in brief, they were used for placement and display of cruets containing water and wine which were mixed during Substantiation for the Mass.

This medieval form spawned a plethora of credence tables and cupboards in oak during the late sixteenth and entire seventeenth centuries : some highly appealing and others merely formulaic.

For the record, the story of the finding of the table and of its present state is as follows :--

The table comprises four separate elements namely the top, capital, column and base. To envisage the state of the table when found by an eagle-eyed, purist antiquarian, turn the top upside down and concrete it onto the upper face of the capital. Now fix a heavy iron pin into the upper face of the top for display of a figure. If this joining had been undertaken by use of lime-based mortar, the top and capital could have been eased/prised apart and the entire table be returned to its original state. However, in order to save the top, the capital was measured, drawn and then sacrificed. The present capital was made as a faithful copy by the former Head Mason of England's most wonderful cathedral ( nominations 'on a postcard' if you wish ). The lifetime experience of the finder enabled identification and rescue but also afforded heartache.

Finally to note, whilst the other three stone tables were ( in some cases still are ) used during the Mass, this is the only one remaining in this design : and hence the only forerunner of later oak examples extant. There is at least one 'pillar piscina' in a West Country church in this same form but the presence of a drain in that confirms its identity to be that of a piscina and not that of a table.

Recovered together with many items of English pewter from a ship which was wrecked in the Caribbean in 1545, this pair of cressets ( floating-wicked lamps ) measuring 3" in height and 4" in maximum diameter are made of cast and wrought copper alloy ( bronze ).

Capable of being suspended from a beam or placed on a flat surface as chosen, it cannot be determined whether they were in transit with the pewter for later domestic use or whether they were for use on board ship. Perhaps, if the organic material which has stained the interior of the cressets could be analysed, it may be learned whether these contained wax or ( whale? ) oil. This however would still not confirm whether they were used on land or sea.

That they now are in such good unrepaired condition belies their recovered state : apparently that of two large, heavily concreted cannon balls.

On the preceding page can be seen the mounts for the handles of each of the cressets : the ends of each handle passing through those side mounts. The alternative manner in which handles were attached was by brazing mounts such as this one to the upper outside surface of each side of a vessel : each mount having a 'depression' on the inner face by which the ends of the handle are retained.

Whilst not always so, such mounts are sometimes formed as heads in a closely similar typical style and form. This fourteenth century example, found very close to Blakeney Priory in Norfolk, is notable both by reason of its exceptionally large size and weight (ten ounces), completeness (they usually are 'snapped off' from the vessel) and excellent condition. One usually distinctive form of vessel with its handle typically mounted in this way is the Situla : used within ecclesiastical environments for holding Holy (ie. blessed) Water. Such vessels usually being relatively small, it is unlikely that this head came from one such.

Because the style of this one is, at one and the same time, both vaguely similar to yet very different from the typical faces of anthropomorphic vessel mounts, it begs the question as to whether most of those surviving are Continental whilst this is English.

That this English fifteenth century 18" high oak figure is of Mary Magdalene is denoted certainly by her traditional long hair and probably by what seems to be a scourge laid across her breast.

Sadly, the most notable characteristic of the carving is its very survival : such figures almost invariably being Continental.

There are two fundamentally different ways in which to make candles : by enrobing wicks that are dipped repeatedly into a vessel containing hot wax or by pouring hot wax into candle-shaped moulds. Whilst the former will have been undertaken by use of vessels now unidentifiable as to purpose, the latter involved use of single or multi-tubed moulds the identity of which is obvious. Whilst such post-medieval moulds for making candles are extant in large numbers, medieval moulds for making candles appear not to have survived. Perhaps this reflects the possible nearly exclusive, habitual use of the dipping process pre-Reformation.

The size of candles used in ecclesiastical environments reflected the desire for overt display : even when paid for by people of modest means. Of materially smaller size will have been votive candles for placement in the home before a picture or image of a person being revered or remembered : whether Godly, Saintly or familial. Whilst candlesticks used in this way are known, as evidenced in this Collection, the moulds for making candles therefor appear not to be : albeit with this one as an exception. Perhaps there are others that, by reason of size and/or apparently indefinable purpose, have gone unrecognised.

Measuring 1 1/2" x 1/2" x 1/4", this Mould, wrought of iron, was used for making small candles for socketed candlesticks : the size of which most likely indicates them having had a votive purpose. For reason of material of manufacture, design and size, it was not used for the moulding at high temperature of ingots in any type of metal. Heated beeswax will have been poured into the Mould until it was half-filled. Following a short period for cooling, a wick will have been laid centrally across the wax with its ends overhanging each end of the Mould. Thereafter, more heated wax will have been used to fill the Mould to its lip. Weighting the ends of the wick as they overhung the Mould will have ensured that it did not move out of place during this second phase of filling. Following final cooling, the candle will have been lifted from the mould by use of the wick ends and, when trimmed, will have been ready for use.

Whilst in good, original condition, the Mould now contains determinedly compacted material that reduces the apparent size of the aperture : and hence the expected size of candle produced therefrom.

On the following page is an unrelated object so ideal for filling a Mould with hot wax as to indicate that it was used for such purpose.

At first observation, this small, wrought lead bowl is of indeterminate specific use : but handling and consideration during a long period has led to a conclusion as to that use.

Each of its physical characteristics, when considered in combination, show it to have been used to heat and pour Candle Wax. Made of lead, measuring 1 1/2"x 1/2" and with a pronounced, circular raised foot and crenellated lip, it becomes apparent that material of manufacture, design and size show it to be a Pan for heating beeswax or tallow ( fat from cooking) : by placing it on a hot hearth and pouring the then-liquid wax into another vessel.

Pouring of hot wax from the Pan into the Candle Mould shown on the previous page is predictable, safe and easy to an extent not apparent from the picture : not least because of the non-obvious pouring spout in the centre of the left hand side. Whilst not acquired together, when placed and considered together the practicability of such a functional relationship between vessels of their type used for this purpose suggests that they evidence such likely, synergetic use from the period.

Exploratory understanding of this unusual object is aided in three ways : by knowing and recognising the significance of its size at about 7"x7"x21/2", its considerable weight at 5lb 3ozs. and by seeing the striking stylistic similarity to aquamanilia.

Despite similarity to those highly atmospheric water dispensers, this is not one but is, in basic terms, a handle which was attached to the lid of a vessel.

Whilst appearing to be made of silver, it is of copper alloy with remains seemingly of gilding and certainly of paint still clearly visible. Beneath the 'base plate' are two threaded bolts: one of iron set into a period copper alloy stem and the other also of iron but brazed directly onto the base plate. The one originally and later the two were the means by which a lid was attached. The combined lid with Handle/Finial was then placed onto a vessel which must have been of a considerable size. The slot which rested over the lip of the vessel when the lid was in place is highly pronounced, has a width of almost half an inch but is not visible in the photograph in its position immediately behind the base plate and behind the back feet of the Beast.

Perhaps a real 'giveaway' to its most probable Asian origin is the mounting position in the top of the head: perhaps for a plume.

As a part of the Collection, whilst obviously early it clearly is alien. It has however been shown in an attempt to attract knowledgeable interest which may aid in establishing provenance. Its design and scale might well evidence its cultural importance but where is it from and what was the purpose of the very large vessel which it crowned? Recent provenance is of its surfacing from very long-term (unpaid!) storage. Whilst hopefully not so, if it is found to be part of another's cultural heritage which has been purloined, it will be returned with alacrity into appropriate safe-keeping.

Made of tin alloy and wrought in the round over an iron staff, the lion projects authority which belie his dimensions of 2"x 1/2"x 3/8". Rearing on his hind legs to grasp the top of a shield, he wears a crown through which can be seen the upper end of the iron rod around which he has been formed. The figure is in complete good order except that just one minute end of the ring which spanned his mouth is extant and that the staff has been truncated below the interface of iron and tin alloy. That he has the face of a man is not unusual from the medieval period, but that his mouth is ringed in combination with that face most certainly is so. Such untypical iconography might be explained by him being a representation of King Richard the Lionheart : the majesty and strength of a lion being tempered by his period in captivity at the beginning of the thirteenth century. Anticipating that he is from a Staff is not untoward, but conjecture as to the context in which the Staff was used and displayed would be unsound.

That cathedrals and many monasteries and churches were large, complex buildings is evidenced by those extant : many of which remain complete but many also now lying in ruins. The faithful communities who lived and worked within these buildings prayed for the population at large, regularly and extensively, in accordance with the strict calendar and practise of the Church. Their forms of worship involved the conducting of small ceremonies : many of which were of modest scale and procedure. In an unpretentious manner, those few engaged in such will have processed to the particular altar or part of the building in order to take part. The present-day equivalent of such processions can be seen in grand ceremonies led by a Celebrant carrying one of the forms of staff in precious metals used therefor : these usually being surmounted by a cross or being in the 'shepherd's crook' form of a Crozier. Such can, however, also be seen in the present day with just a few worshipping in a formal but modest manner before a side altar of a cathedral.

No flight of fantasy is required to envisage this finial, when affixed to a staff, being used frequently to lead small, pre-worship processions. At its size of 2"x 1 3/4"x 3/4", that it came from and was used in a modest establishment is most likely. Whilst it is known that it was found in the vicinity of Brockdish, Norfolk, provenance to a specific building or community is not known. When seen and handled, whilst robust beyond expectation generated by the photograph, it exudes humble monasticism.